“We (the Supreme Court), are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final,” said American jurist and writer Robert H Jackson famously. Our own legendary jurist V R Krishna Iyer was so fond of this statement that he used to quote it often. November 9’s historic judgement of the constitutional bench of the Supreme Court of India on the Babri Masjid/Ram Janmabhoomi conundrum once again brings to mind the nature of justice in relation to the finality of legal dispensation.

The judgement has been generally accepted and even welcomed by the majority of the public and the political class. Even some Muslim organisations (apparently the aggrieved faction) have expressed a sense of relief in achieving a closure of sorts for this long-drawn legal battle. That this judgement can still be challenged and a review petition filed is not likely to alter the ground reality (no pun intended), considering the fact that this was a unanimous verdict by a five-member bench. However, many significant questions still remain unanswered.

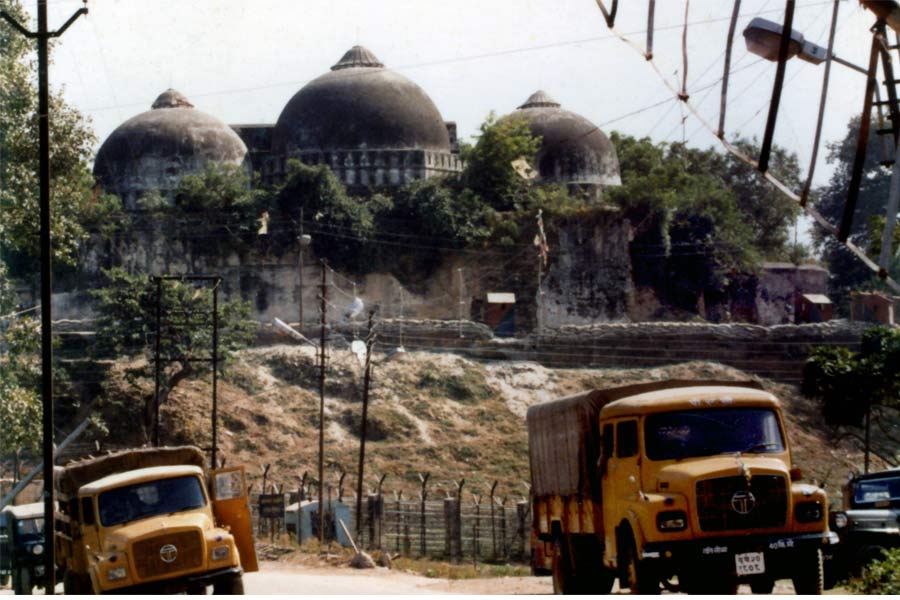

The judgement, spread over a thousand pages, is very complex (complicated, some would argue). It makes it unequivocally clear that the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, was “an egregious violation of the rule of law” as also “a calculated act of destroying a place of public worship.” But the honourable bench does not believe in righting this wrong by rebuilding the Masjid at the very site. Instead, the whole area of 2.77 acres will now be handed over to a trust for the construction of a Ram temple. Doesn’t this, one wonders, validate in a sense the very premise/motive of the ‘egregious violation of law’? After all, this is exactly what the VHP and other Hindutva groups have always wanted to do—demolish the masjid and build a temple instead. The first part was carried out in 1992. And now, 27 years later, it has become possible and legal to realise the second.

A related concern that crosses the mind is about the perpetrators of that ‘egregious violation’. Will there be a comprehensive and unambiguous legal action against them, now that their crime has been reiterated in the final judgement as well? (A CBI court has been hearing that case all these years and we will have to keep waiting for its closure, if and when it happens). How does one understand the response of Shri L K Advani, who had led the Ram Janmabhoomi movement for many years and is also among the prime accused of the demolition case? He said yesterday that he “stood vindicated”. Really? Vindicated for an egregious violation of the rule of the law — how cool is that?

Several analysts think that the Supreme Court judgement appears more like an expression of political compromise than an assertion of unambiguous legality. In fact, the Court had repeatedly explored the possibility of a negotiated settlement outside its own purview. When that did not materialise, and when it was compelled to give a final verdict, this is what it offers, a judgement that caters to the concerns of all the parties.

It’s interesting in this context to recall an observation made by another five-member bench of the Supreme Court (led by the then Chief Justice M N Venkatachaliah) during the judgement of October 1994. Rejecting the Presidential reference on the Ayodhya dispute, the Court said: “We have no doubt that the moderate Hindu has little taste for the tearing down of the place of worship of another to replace it with a temple. It is our fervent hope that moderate opinion shall find general expression and that communal brotherhood shall bring to the dispute at Ayodhya an amicable solution long before the Courts resolve it.” Well, 25 years later, it appears we have come a long way. The moderate Hindu’s taste has changed and the Courts have forced an ‘amicable solution’ on both sides.

One gets the feeling that there are two major reasons why this judgement has generally been welcomed. One, it brings some kind of closure to an old and very complicated dispute. Two, it has something for everyone. By allowing a temple to be built at the very place where a masjid stood, the Hindus get everything they asked for. And instead of 2.77 acres and a 450-year-old building that they lost, the Muslims will get 5 acres where a big new masjid can be built. This judgement will not, therefore, provoke inflammatory responses as a one-sided judgement would have done. The ideal outcome for everyone is to accept this as an amicable solution and move on in life. While the feel good factor is obvious, not everyone is convinced of the legal soundness of the judgement.

A related concern that objective analysts have about yesterday’s judgement is its implication on similar cases in the future. If the courts can make conclusive judgements on matters of belief, such as the exact location of a mythological place or whether a deity/divine entity can be treated as a legal party (juridical person), where do we draw the line? Do metaphysical notions and religious sentiments constitute legal points or evidence? What about the Sabarimala issue where there is a fundamental clash between constitutional rights (of gender equality) and religious convictions about traditional customs?

The biggest concern perhaps is whether this judgement will encourage agents of bigotry to try their luck elsewhere. The fear that whether this judgement will open the mythological Pandora’s box. It was certainly not an easy task for the Supreme Court which, by its own admission, was “called upon to fulfil its adjudicatory function where it is claimed that two quests for the truth impinge on the freedoms of the other or violate the rule of law.” The big question is whether the violation of the rule of law was overlooked in favour of the quest for imaginary truths? We will certainly hear more on this from legal experts in the days ahead.

In December 1992, Hindutva activists on their way home after demolishing the Babri Masjid were heard shouting:

“Yeh sirf jhanki hai,

Kashi, Mathura baaki hai”

(this is just a trailer, Kashi, Mathura still to come).

One of their leaders, former MP Vinay Katiyar—another key accused in the Babri Masjid demolition case—had openly talked about pursuing the “unfinished agenda” of Kashi just last week (a few days before the Supreme Court judgment). Speaking to the media, the BJP leader said, “We are waiting for the Supreme court verdict. After that, we will build the Ram temple in Ayodhya and then will also move towards liberating the Kashi and Mathura temples”. One hopes the honorable Supreme Court will see to it that its judgement, delivered with the express intention of bringing about peace and communal harmony, is not appropriated by vested interests to unleash on the nation another cycle of needless violence. One hopes the spirit of the judgement is upheld, even when one may have differences with the details.

Let’s return to the October 1994 judgement. While explaining the logic of rejecting the Presidential reference on the Ayodhya dispute, the Supreme Court also said something about itself: “Ayodhya is a storm that will pass. The dignity and honour of the Supreme Court cannot be compromised because of it.” 25 years later, the storm of Ayodhya has now been contained, one hopes. As for protecting the honour and dignity of the Supreme Court, well, posterity will decide if yesterday’s judgement can help the cause.

Cover Image: P Musthafa