This year in Kerala, the South West Monsoon was delayed by a week. According to the weatherman, the rain, so far, is normal compared to the previous monsoons. However, the killer waves along the Kerala coast are anything but normal.

In Valiyathura, a coastal village in Thiruvananthapuram, the killer waves have swallowed some 100 houses forcing fishermen to take shelter at a nearby Government Upper Primary School. The school is less than 500 meters away from where their houses stood once but they have been bestowed with a new name. They have become refugees in their own village.

Being refugees

According to Saju Antony, an activist among the fishermen community, fishermen losing houses and livelihood every monsoon has become a new norm.

“As seashore erosion is happening rapidly due to manmade activities like unscientific construction of artificial harbours and ports to modernise the coast and make it economical, fishermen are not only losing their livelihood but their homes too. They become refugees in their own land. Being haunted by uncertainty, they are forced to take shelter in nearby schools and community halls, where every meal has become a challenge,” Saju added.

In an ordinary classroom of the Govt UP School, some 35 families, including aged people and children, are forced to stay. There are no proper mattresses, lights or fans. There are no proper cooking areas too. And worse, there is only one toilet for the 300 people.

“We were leading a decent life in a decent house, for which we were paying taxes. When I came to the house after my marriage some 17 years ago, the high tide line was a good 250m to 300m away from our home. Unfortunately, year after year, the seashore has started to vanish. And during the last five years, it happened at a fairly quick clip. This year, the distance between the house and the high tide line has alarmingly reduced to just 50m. We knew that the house would be hit. But we never thought that it would be swallowed whole by the waves,” 35-year-old Bindu Alosious told The Kochi Post.

“All of a sudden, we have become refugees. And the uncertainty is haunting us. At the camp, I discovered others like me—these people have been staying here for the last three years without any help from the government. If there are such cases still waiting for help, what would be our fate? Are we going to get any relief from the government anytime soon? We may have to continue here indefinitely…,” Bindu says while wiping away the tears.

Manmade Activities

Telma, Agnes, Mariamma and others had similar tales to tell. Only the date and time of the loss of property differed. However, everyone’s woes seemed to stem from sea erosion. They infer the reasons for sea erosion are manmade activities.

“We all were born on this coast. We know how far away the high tide line was some 30 years ago. But after the construction of Vizhinjam Harbour and the ongoing construction of Adani Group’s Vizhinjam International Sea Port, the seashore has been receding drastically. In the old days, the waves would take our shore, but the same waves would it bring it back too. It was a cycle. And of course, the waves were less furious then. Now, the furious waves are eating away our shore and our houses,” Agnes M, 55, told The Kochi Post.

“We all were born on this coast. We know how far away the high tide line was some 30 years ago. But after the construction of Vizhinjam Harbour and the ongoing construction of Adani Group’s Vizhinjam International Sea Port, the seashore has been receding drastically. In the old days, the waves would take our shore, but the same waves would it bring it back too. It was a cycle. And of course, the waves were less furious then. Now, the furious waves are eating away our shore and our houses,” Agnes M, 55, told The Kochi Post.

“Huge stones were dropped in Vizhinjam Sea to stop waves from eroding the Vizhinjam Harbour. And now, again stones are dropped for Adani’s port. Eventually, the waves shift to our area, Valiyathura, with more intensity and strength. They devour everything in their way–our shore and houses,” Agnes added.

In 2018, some 300 houses were damaged during the monsoons. According to Joseph Vijayan, an activist who has been relentlessly campaigning against unscientific construction activities on the coast for three decades, all seashore erosions happened only because of manmade activities.

Valiyathura, one of the most affected villages, has seen seashore erosion along with fishermen losing houses. Joseph concurred with the fishermen. “It is the construction of Vizhinjam Harbour, on-going construction of the $6.5 million Vizhinjam International Sea Port and dropping of huge stones to stop waves in that area which is causing damage to coast of Valiyathura,” Joseph said.

“The playground where I played football now lies somewhere deep on the seabed. Day by day, I see the seashore disappear right before my eyes,” Joseph added.

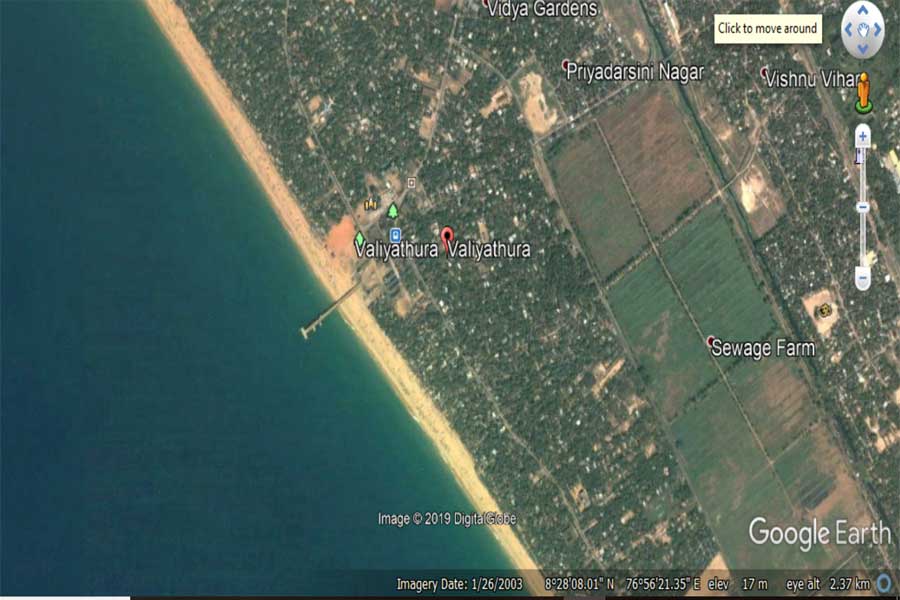

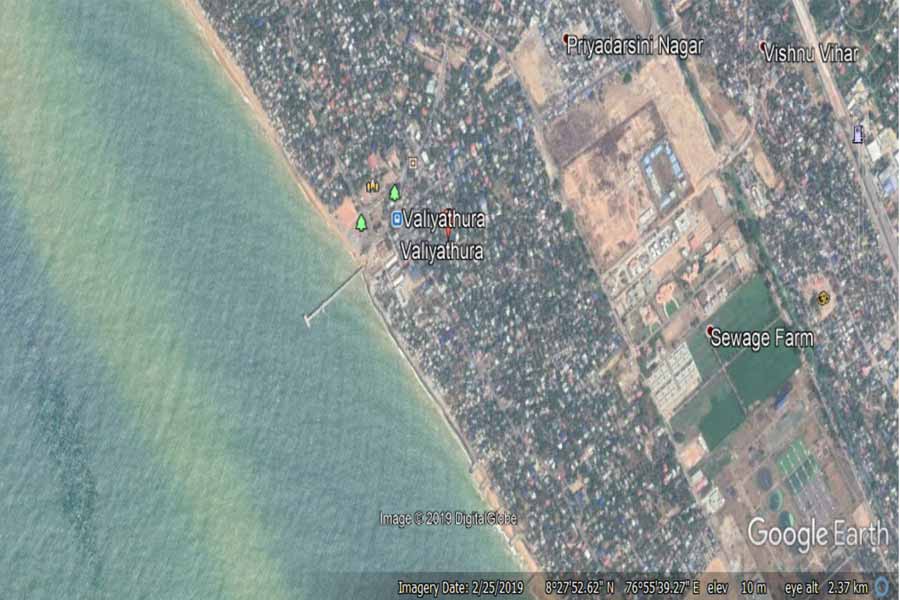

Speaking about the Chellanam seashore erosion, Joseph said that the construction of a fishing harbour nearby had added to the problem. To validate his point, Joseph produced two Google Earth pictures of Chellanam area taken in 2011 and 2019.

While agreeing that the construction of fishing harbour would have helped a lot of fishermen in that area, Joseph argues that the government forgot to take into account those living in nearby coastal areas and the effect of the harbour construction on their lives. Joseph added that dropping huge stones and making artificial walls unscientifically to stop waves will only worsen the situation.

Almost one-third of India’s 6,632km coastline was lost to soil erosion between 1990 and 2016, said a National Centre for Coastal Research report. The report, National Assessment of Shoreline Changes along Indian Coast, which mapped the shoreline changes along the Indian coast for the last 26 years, found that the West Bengal coast (63%) was the most vulnerable to erosion followed by Puducherry (57%), Kerala (45%) and Tamil Nadu (41%). The jetties, fishing harbours and ports are constructed at many coastal sites for the purpose of development. Construction of any structure on the coast naturally causes erosion in the downdrift and accretion in the updrift side.

CRZ Killing Coast

Meanwhile, T Peter, General Secretary of the National Fishworkers Forum (NFF), said that the new CRZ issued to help industrialists, especially those in the tourism sector, will damage the coast with increased vigour. The Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) notification of 2019 was approved by the Union Cabinet and replaced the then existing norms of CRZ (2011) on January 18. The new notification contains certain drastic changes such as sanction of land reclamation in the intertidal zone and shrinking of the No Development Zone (NDZ).

While the government stated that the new notification “will lead to enhanced activities in the coastal regions thereby promoting economic growth while also respecting the conservation principles of coastal regions,” Peter claims that it is a total eyewash. It is a dilution of the CRZ notification of 2011, which was meant to protect the coastal ecology and livelihoods of coastal inhabitants like fisherfolk.

“Already the seashore erosion due to manmade activities is threatening the livelihood of fishermen. When the new CRZ kicks in, construction will expedite along the coast. By the way of the Sagarmala Project, some 550 projects will be put in place along the Indian coast. And it will kill the coast and the coastal community,” Peter added.

Pointing out that the previous CRZ allowed construction activities in the coast only beyond a distance of 200 metres from the HTL, Peter said “the new CRZ notification allows construction activities at a distance of 50 metres from the HTL. This is going to affect the livelihood of fishermen and the coast’s ecology.” He added that the new coastal regulations have been drafted only for the easy implementation of the Sagarmala Project, initially proposed in 2003, during the Atal Bihari Vajpayee- led NDA government.

“In some 20 years, Kerala is going to lose its coast entirely. And traditional fishermen will vanish. Already we are seeing its signs. The younger generation is now moving into service sector jobs as fishing as a vocation is becoming unviable,” said Peter. “More and more refugees will be created. And more and more schools will be filled with fishermen. They will be struggling with poverty and living in uncertainty,” he added.