The law against Sedition or Seditious Libel has been in existence for hundreds of years and is a remnant of the monarchial rulers. In India, the law of sedition is the legacy of the colonial rule in the form of Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), 1860 which defines the offence of sedition as an offence when a person “by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law in India”.

In simple terms, Oxford English Dictionary defines sedition as “actions or speech which encourages rebellion against the authority of a state or ruler”. The law of sedition therefore takes within its ambit myriad forms of expressions and is often found to be infringing upon the precious freedom of speech and expression guaranteed under the Constitution.

At a time when it was necessary to defend the government from any act of rebellion or any feeling that might have led to a rebellion, the law of sedition or seditious libel was used by the English monarchy. However, it is encouraging to note that even at that time there were voices opposing the applicability of sedition law.

Therefore when Thomas Paine, the acclaimed philosopher and political activist in colonial America, published the second volume of his book titled Rights of Man in 1791-92 putting forth the doctrine that popular political revolution was permissible in situations where a government or a ruler fails to defend the natural rights of its people, he had found himself being prosecuted for seditious libel.

Paine was defended by the noted American lawyer Thomas Erskine, who in his defense made a thorough speech to the Jury regarding the freedom of thought, the freedom of Press and the actual intent of the author in inciting an insurrection against the monarch as distinguished from advancing a doctrine to defend the rights of the populace.

The following excerpt from Erskine’s speech before the jury at the Old Bailey (The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales) is reflective of the idea that when it comes to freedom of thought and speech as compared to seditious expressions, the same has to be weighed carefully on the pedestal of intention, and with the attempt to analyse whether such remarks or comments are meant for improvement of the weaknesses of a State by critically identifying them or to intentionally and deliberately incite an insurrection against the State:

“What crime then is charged upon this man? That he has written and published this book, and that this book is hostile to the Constitution of England?—No. The law of England knows no such crime. It must be proved, in order to constitute his guilt, not whether the Attorney General approves the book—not whether you approve the book—but whether Paine did not sit down and write a book against a Constitution which he admired and loved, with the diabolical intention of provoking discord and sedition in the country. If this were proved, Thomas Paine could not be defended; but if he thinks, what I and you do not think, that the Constitution of England is not the best calculated to promote the happiness of the people of this country, he is not guilty of any offence against the law, though his opinions may be inconsistent with the principles of the Constitution. Every man is protected in his opinions; it is only conduct that makes guilt.”

Though Thomas Paine was still convicted by the grand jury despite his moving speech, Erskine was hailed by the supporters and advocates of freedom of speech and the Press.

The ideas put forth by Erskine relied wholly upon the fundamental idea that it is not the opinion of the state or the prosecution which should establish a particular uttering as seditious libel but there should be enough proof to show that the person accused of it had actually intended to incite violence or an insurrection against the State. This idea, however, despite having been advocated more than 200 years ago, still does not find the support of the prosecutors and the governments that seek to utilize the law of sedition.

In India the law of sedition has a particular history and relevance in the context of the freedom struggle and the authoritarian colonial rule, which has to be understood while dealing with the issue.

Section 124 A of the IPC along with other legislations, which have now been repealed, such as the Vernacular Press Act, 1878, the Newspapers (Incitement of Offences) Act, 1908, and the Indian Press Act, 1910 – made the legal framework for the British Government to silence any form of revolution or expression that went against it.

Sedition was the iron hand used by the British Colonialists to suppress any dissent or thought that would have led to revolution or an uprising in the Indian soil ruled by them. Therefore, most of the freedom fighters of the Indian independence struggle had been charged and jailed under this provision.

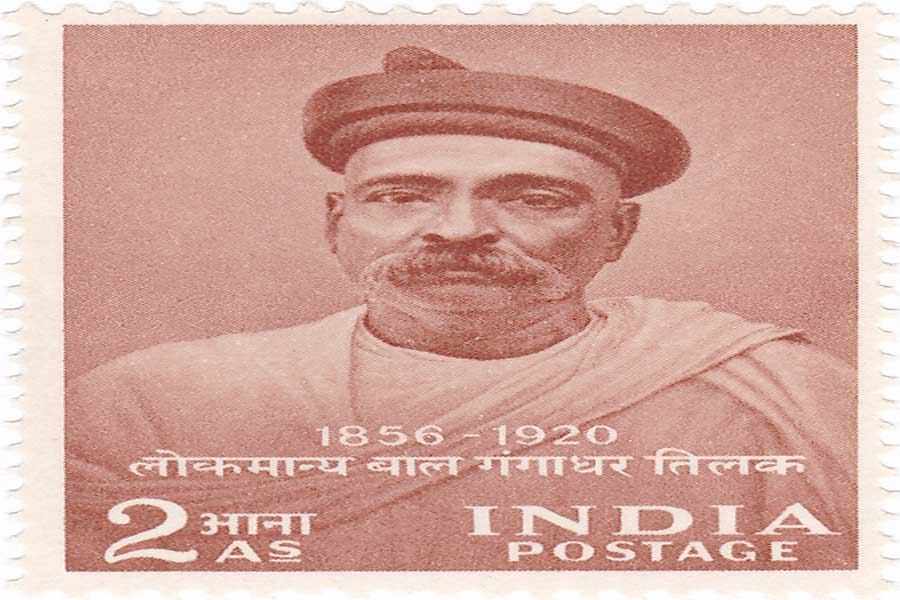

Perhaps the first case of Sedition in India would be the Queen Empress v. Jogendra Chunder Bose (1892). The next would be the case of Queen Empress v. Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1897) where disaffection had been defined to mean hatred, enmity, dislike, hostility, contempt and every form of ill-will to the Government.

In the case against Lokmanya Tilak, the jury made it clear that the intensity of the disaffection was absolutely immaterial. Whether there was any person who had been proved to have been excited by such speech was also termed as immaterial. Whether such a speech led to a mutiny or rebellion or any kind of disturbance, great or small, was also treated as an immaterial consideration.

Strachey J., while explaining the charge to the jury observed that “… if you find that either of the prisoners has tried to excite such feelings in others, you must convict him even if there is nothing to show that he succeeded.” As a result, the Jury, by a majority of six to three, found the legendary Bal Gangadhar Tilak guilty. In years to follow, a number of freedom fighters were charged and imprisoned under this law including Annie Besant and Mahatma Gandhi.

However, despite the aforesaid experiences with the law of sedition, it was retained by Independent India but proponents who advocate striking down of the draconian provision remained and still remain. Many see it as an unnecessary barrier to the freedom of speech in the modern democracy that is based on a positive criticism of the state and holding one’s leaders accountable for their actions.

The constitutionality of Section 124 A and Section 505 of the IPC came before the Supreme Court in 1962 in the case of Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar. The Court held that “the provisions of the sections read as a whole, along with the explanations, make it reasonably clear that the sections aim at rendering penal only such activities as would be intended, or have a tendency, to create disorder or disturbance of public peace by resort to violence.”

By these words, therefore, the Supreme Court limited the application of the provision to acts involving intention or tendency to create disorder, or disturbance of law and order, or incitement to violence.

However, the sad truth remains that while this interpretation can be relied upon and the courts would interfere if the State imposes the provision on a person who had not intended to create any violence or disaffection towards the country, the same is being used as a tool for silencing political opponents, activists, artists, authors and journalists alike—be it Arundhati Roy for expressing her opinion or Bhima Koregaon activists. In January this year, an 80-year-old writer Hiren Gohain, activist Akhil Gogoi and journalist Manjit Mahanta were arrested in Assam for sedition, as they opposed the Central Government in bringing forth the controversial Citizenship Amendment Bill. The Delhi Police also filed a chargesheet against Kanhaiya Kumar and others in the infamous JNU sedition case. A clear pattern is emerging.

Between 2014 and 2017, almost 165 people were arrested for sedition, including Patidar activist Hardik Patel. In most cases the courts have intervened and cases of sedition do not necessarily end in conviction but the purpose of the ruling government in stifling any opposition, dissent or criticism against it is fulfilled by merely charging such offenders and arresting them.

With the term “anti-national” being invoked in political rallies by the ruling regime and the systematic abuse of this provision in the cases of activists in Assam and JNU, some of whom are candidates opposing the ruling government in the 2019 General Elections, serious questions are being raised as to the viability of such a colonial and draconian law in the present era of constructive democracy which allows dissent, criticism and freedom of speech and expression.

Perhaps it was the fear of this systematic abuse of the law by the future governments that had made Mahatma Gandhi term the provision as “rape of the word ‘law’ ”. According to Gandhi, the provision was an absolute measure to suppress liberty. He further said: “Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by the law. If one has no affection for a person, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote or incite to violence.”

One can only hope our lawmakers take heed of the same and remove this curse of colonial oppression from our statute book now.